Criteria used

![Ver [Bibliographic references by centuries and dates] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Bibliographic references by centuries and dates

Conservation and use criteria by year

-

< 1850:

- < 1800: Strictly “antique” books. Laid paper, inks, and bindings are sensitive. Occasional, controlled use. Recommended placement: protected area and preferably stored horizontally.

- 1800–1850: Transitional period. Still considered antique books, though somewhat more robust. Moderate use. Placement: protected area; vertical only if the spine is in good condition.

-

≥ 1850:

- 1850–1900: Historic books from the industrial era. Paper is sometimes acidic, but the structure is generally more stable. Normal use with basic care. Placement: visible, accessible area; vertical shelving.

- ≥ 1900: Modern books. Standardized industrial materials. Free and frequent use. Placement: visible, accessible area; vertical shelving.

Index grouped by centuries and ordered by dates

Index of bibliographical references, including the armorials rolls, grouped by centuries and ordered by dates:

Century I B.C.:

- [Catullus, C. V.; Century I B.C.]: Corpus Catuliano, 116 Poems: Poem number 62, Wedding Hymn in Hexameters.

Century XI:

- [Cnut Gospels; 1020]: The Cnut Gospels.

Century XII:

- [Fernando II de León; 1167]: Carta Puebla de Benavente.

- [Fernando II de León; 1181]: Privilegio de Ampliación del Alfoz de Benavente.

Century XIII:

- [Wijnbergen; 1265]: Wijnbergen Armorial.

- [Alfonso X of Castile; 1265]: The Seven-Part Code.

- [Heralds' Roll, T.; 1280]: The Heralds' Roll.

- [Charles' Roll; 1285]: Charles's Roll.

- [St. George's Roll; 1285]: MS Vincent, 164 ff.1-21b.

- [Vincent, MS; 1285]: MS Vincent, 164 ff.1-21b.

- [Marshal, L.; 1295]: The Lord Marshal's Roll.

- [Febrer, J.; Century XIII]: Trovas de Mossen Jaime Febrer: que tratan de los conquistadores de Valencia.

Century XIV:

- [Manesse; 1315]: Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift.

- [Aix-en-Provence; 1351]: Délibérations municipales d'Aix-en-Provence.

- [Pedro IV de Aragón; 1353]: Ordinance made by the very high and excellent Prince and Lord Lord Don Pedro the third King of Aragon, on the manner in which the Kings of Aragon will be consecrated and they themselves will be crowned.

- [Gaio da Legnago, A. del; 1375]: Catulli Veronensis Liber Incipit, Manuscript.

- [Cofradía de Santiago; Century XIV]: Libro de la Cofradía de Caballeros de Santiago de la Fuente.

Century XV:

- [Bergshammars; 1440]: Roll of arms.

- [Ingeram, H.; 1459]: Ingeram Codex.

- [Edward IV of England; 1461]: The Armorial of Edward IV.

- [Ortenburg; 1473]: Ortenburg Armorial.

- [Grünenberg, K.; 1480]: Das Wappenbuch Conrads von Grünenberg, Ritters und Bürgers zu Constanz.

- [St. Gallen; 1480]: Wappenbuch des St. Galler Abtes Ulrich Rösch.

- [Anonymous; 1490a]: Armorial des chevaliers de la Table ronde.

- [Marchant, G.; 1499]: Compost et Kalendrier des Bergères.

- [Urfe; Century XV]: Urfe's Armorial.

Century XVI:

- [Calvo, P.; 1501]: Libro de cuentas de la ciudad de Calatayud.

- [Cró, J. do; 1509]: Livro do Armeiro-Mor.

- [Fernández de Enciso, M.; 1519]: Sum of Geography, which deals with all the parts and provinces of the world: especially the Indies. And deals extensively with the art of navigation, together with the sphere in the vernacular, with the regulation of the Sun and the North: newly made. With royal privilege..

- [Godinho, A.; 1521]: Livro da nobreza e da perfeição das armas dos reis cristãos e nobres linhagens dos reinos e senhorios de Portugal.

- [Lutzelbourg, N. de; 1530]: Roll of arms.

- [Bosque, J. del; 1540]: Libro de Armería del Reino de Navarra.

- [Raber, V.; 1548]: Armorial con 7244 escudos de armas.

- [Paradin, C.; 1557]: Devises heroïqves.

- [Argote de Molina, G.; 1588]: Nobleza de Andalucía.

- [Portolés, J.; Molino, M. del; 1590]: Scholiorum Sive Adnotationum ad Repertorium Michaelis Molini Super Foris et Observantiis Regni Arago.

- [Gamonal; Century XVI]: Libro en que se pintan los cavalleros cofrades de la Cofradía de Nuestra Señora de Gamonal.

- [Pérez de Vargas, J.; XVI]: Nobiliario.

- [Rodríguez de la Vega, A.; XVI]: Roll of arms of Spain.

- [Avilés, T. de; XVI]: Roll of arms.

- [Rodríguez de Lena, P.; Century XVI]: Libro del passo honroso defendido por el excelente cavaliero Suero de Quiñones.

- [Ma, F.; Century XVI]: Genealogy of the Mǎ Family, 馬民家记.

Century XVII:

- [Cervantes Saavedra, M. de; 1605]: El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha.

- [Shakespeare, W.; 1608]: Coriolanus.

- [Rio, M. del; 1608]: Disquisitionum Magicarum Libri Sex: Quibus continetur accurata curiosarum artium et vanarum superstitionum confutatio, utilis Theologis, Jurisconsultis, Medicis, Philologis.

- [Takamiya; 1620]: Heraldic manuscript of the English kings and peers.

- [Petra Sancta, S.; 1634]: De symbolis heroicis.

- [Mogrovejo de la Cerda, J.; 1636]: Árbol de los Veras compuesto por Alonso López de Haro, Criado de Su Majestad y Ministro de su Real Consejo de las Órdenes y Cronista de los Reinos de Castilla y León.

- [Salazar y Mendoza, M. de; 1640]: Formulario de armas.

- [Salazar y Mendoza, M. de; 1654]: Nobiliario de armas.

- [King, D.; 1656]: The Vale-Royal of England or, The County Palatine of Chester Illustrated, wherein is Contained a Geographical and Historical Description of that Famous County, with all its Hundreds and Seats of the Nobility, Gentry and Freeholders.

- [Menestrier, C. F.; 1659]: Le veritable art du blason et la pratique des Armoiries depuis leur Institution.

- [Martineau du Plessis, D.; 1700]: Nouvelle Géographie.

- [Tewkesbury; Century XVII]: Founder's and benefactors' book of Tewkesbury abbey.

- [Galdiano L.; Century XVII]: Arms and Lineages of Spain.

- [Tejero de Rojas y Sandoval, J. F.; XVII]: Linajes de Aragón, Castilla, León, Galicia, Cataluña, Navarra y Vizcaya.

Century XVIII:

- [Vega, P. J. de; 1702]: Compendio de la Maior Parte Ð los Blassones, Armas, e Ynsignias Ð las Ylustres Casas, Familias, y Apellidos del Reyno Ð Navarra i Parte Ð la Provincia de Gvipvzcoa, Segvn las Vsan y Traen los Svccesores Ðellas.

- [Stych, F. S.; 1722]: The Flow Chart Method and Heraldic Enquiries.

- [Nisbet, A.; 1722]: System of Heraldry Speculative and Practical: With the True Art of Blazon.

- [Avilés, J.; 1725a]: Ciencia heroyca, reducida a las leyes heráldicas del blasón: Ilustrada con exemplares de todas las piezas, figuras y ornamentos de que puede componerse un escudo de armas interior y exteriormente, Volume I.

- [Avilés, J.; 1725b]: Ciencia heroyca, reducida a las leyes heráldicas del blasón: Ilustrada con exemplares de todas las piezas, figuras y ornamentos de que puede componerse un escudo de armas interior y exteriormente, Volume II.

- [Menestrier, C. F.; 1750]: La Nouvelle Methode Raisonnée du Blason pour l'Aprendre d'une Maniere Aisée: Reduite en Leçons par Demandes, Et par Réponses.

- [Porny, M. A.; 1765]: The Elements of Heraldry.

- [Avilés, J.; 1780a]: Ciencia heroyca, reducida a las leyes heráldicas del blasón: Ilustrada con exemplares de todas las piezas, figuras y ornamentos de que puede componerse un escudo de armas interior y exteriormente, Volume I.

- [Avilés, J.; 1780b]: Ciencia heroyca, reducida a las leyes heráldicas del blasón: Ilustrada con exemplares de todas las piezas, figuras y ornamentos de que puede componerse un escudo de armas interior y exteriormente, Tomo II.

- [Pineda, Juan d.; 1783]: Libro del Passo Honroso, defendido por el excelente caballero Suero de Quiñones.

- [Moreno de Vargas, B.; 1795]: Discourse on the Nobility of Spain.

- [Costa i Cases, P.; Century XVIII]: Nobiliario catalán.

- [Anonymous; 1800a]: Armerías de España.

Century XIX:

- [Nisbet, A.; 1816]: System of Heraldry Speculative and Practical: With the True Art of Blazon.

- [Lindsay, D.; 1822]: Facsimile of an Ancient Heraldic Manuscript Emblazoned by Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount, Lyon King of Arms, 1542.

- [Lainé, P. L.; Lainé, J. J. L.; 1828]: Archives généalogiques et historiques de la noblesse de France, ou, Recueil de preuves, mémoires et notices généralogiques, servant à constater l'origine, la filiation, les alliances et lés illustrations religieuses, civiles et militaires de diverses maisons et familles nobles du royaume; Avec la collection des nobiliaires généraux des provinces de France.

- [Burke, J.; 1836]: A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland: Enjoying Territorial Possessions or High Official Rank; but Uninvested with Heritable Honours.

- [Burke, B.; 1842]: The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales; Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time.

- [Medél, R.; 1846]: The Spanish Blazon or Heraldic Science, Coats of Arms of the Different Kingdoms into which Spain has been divided, and of the Noble Families thereof.

- [Parker, J. H.; 1847]: A Glossary of Terms Used in British heraldry, with a chronological table illustrative of its rise and progress.

- [Dufour, A. H.; 1850]: Plan of Madrid.

- [Osmont, C.; 1858]: L'Art Heraldique Contenant La Maniere d ' Apprendre Facillement Le Blason, Enrichy Des Figures Necessaires Pour L' Intelligence Des Termes.

- [Piferrer, F.; 1858]: Treatise on Heraldry and Blazonry.

- [Costa y Turell, M.; 1858]: Tratado completo de la ciencia del blasón, o sea, Código heráldico-histórico; acompañado de una estensa noticia de todas las órdenes de caballería existentes y abolidas.

- [Rietstap, J. B.; 1861]: Armorial général, précedé d'un Dictionnaire des termes du blason.

- [Bécquer, G. A.; 1862]: The Mount of the Souls.

- [Langton, W.; 1876]: The Visitation of Lancashire and a part of Cheshire, made in the twenty-fourth year of the reign of King Henry the Eighth, A.D. 1533, by special commission of Thomas Benolte (Benalt), Clarencieux.

- [Stodart, R. R.; 1881]: Scottish Arms: Being a Collection of Armorial Bearings, A.D. 1370-1678.

- [Husenbeth, F. C.; 1882]: Emblems of saints: by which they are distinguished in works of art.

- [Rylands, J. P.; 1882]: The Visitation of Cheshire in the Year 1580, Made by Robert Glover, Somerset Herald, for William Flower, Norroy King of Arms, with Numerous Additions and Continuations, Including those from The Visitation of Cheshire in the Year 1566, by the same Herald, with an Appendix Containing The Visitation of a Part of Cheshire in the Year 1533, William Fellows, Lancaster Herald, for Thomas Benolte, Clarenceux King Of Arms, And a Fragment of The Visitation of the City of Chester in the Year 1591, Made by Thomas Chaloner, Deputy to the Office Of Arms.

- [Gourdon de Genouillac, H.; 1889]: L'Art Héraldique.

- [Ströhl, H. G.; 1891]: Die Wappen der Buchgewerbe.

- [Winkler, P. P. von; 1892]: Russian Heraldry: History and Description of Russian Coats of Arms with Illustrations of All the Coats of Arms of the Nobility, included in the General Armorial of the Russian Empire.

- [Parker, J.; 1894]: A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry, a New Edition with one Thousand Illustrations.

- [Stock, E.; 1895]: The Antiquary, A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past.

- [Wade, W. C.; 1898]: The symbolisms of heraldry or A treatise on the meanings and derivations of armorial bearings.

- [Rumor, S.; 1899]: Il Blasone Vicentino Descritto ed Illustrato.

Century XX:

- [Uhagón y Guardamino, F. R.; 1904]: Libro de la Cofradía de Caballeros de Santiago de la Fuente, Fundada por los Burgaleses en Tiempo de Don Alfonso XI.

- [Durasov, V. A.; 1906]: Heráldica de la Nobleza de toda Rusia.

- [Fox-Davies, A. C.; 1909]: A Complete Guide to Heraldry.

- [Armytage, G. J.; Rylands, J. P.; 1909]: Pedigrees Made at the Visitation of Cheshire, 1613, taken by Richard Saint George, Esq., Norroy King of Arms and Henry Saint George, Gent., Bluemantle Pursuivant of Arms; and some other contemporary pedigrees.

- [Liñán y Eguizábal, J. de; 1911]: Armorial of Aragon.

- [Cramer, R. de; 1913]: Drapeaux, Bannières, Vlaggen en Wimpels.

- [Iguiniz, J. B.; 1920]: The National Coat of Arms: A Documented and Illustrated Historical Monograph.

- [García Carraffa, A.; García Carraffa, A.; 1920]: Heraldic and Genealogical Dictionary of Spanish and American Surnames.

- [Mayer, L. A.; 1933]: Saracenic Heraldry: A Survey.

- [Bravo Guarida, C.; 1934]: El Paso Honroso de Don Suero de Quiñones: Célebre Caballero Leonés en el Puente de Órbigo, en 1434.

- [Adams, A.; 1941]: Cheshire Visitation Pedigrees, 1663.

- [Finas, F.; 1950]: Collection des blasons de France. 1st Edition.

- [Moncreiffe, I.; Pottinger, D.; 1953]: Simple Heraldry.

- [Vicente Cascante, I.; 1956]: General Heraldry and Sources of the Arms of Spain.

- [Nieto y Cortadellas, R.; 1957a]: La Generala Santander y sus parientes habaneros los Pontón.

- [Atienza y Navajas, J. de; 1959]: Nobiliario Español: Diccionario Heráldico de Apellidos y Títulos.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 1963]: A Leónese Heraldic Embroidery: the Carbuncle in Medieval Coats of Arms.

- [Sánchez Albornoz, C.; 1965]: La auténtica batalla de Clavijo.

- [Scott-Giles, C. W.; 1965]: Some Arthurian Coats of Arms.

- [Sarandeses Pérez, F.; 1966]: Heraldry of Asturian Surnames.

- [Parker, J.; Gough, H.; 1966]: A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry, a New Edition with one Thousand Illustrations.

- [García Carraffa, A.; García Carraffa, A.; 1968]: El Solar Catalán, Valenciano y Balear.

- [Cuena Bartolomé, J.; 1968]: The ordered trial of solutions in hydraulic systems by means of mathematical simulation models on an electronic computer.

- [González Echegaray, M. C.; 1969]: Escudos de Cantabria.

- [Toral y Fernández de Peñaranda, E.; 1970]: The Coat of Arms of the City of Úbeda: Notes for a Historical Study.

- [Parker, J.; 1970]: A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry, a New Edition with one Thousand Illustrations.

- [Parker, J.; 1971]: A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry, a New Edition with one Thousand Illustrations.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 1974]: Book of Armory of the Kingdom of Navarra: Transcription and Study.

- [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1975]: Fundamentos de Heráldica (Ciencia del Blasón).

- [Neubecker, O.; 1976]: Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning.

- [Labandeira Fernández, A.; 1977]: The Passo Honroso of Suero de Quiñones. Introduction and edition by Amancio Labandeira Fernández.

- [Chaparro D'Acosta L.; 1979]: Heráldica de los Apellidos Canarios.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 1982]: Medieval Spanish Heraldry I: The Royal House of Leon and Castile.

- [Martinena Ruiz, J. J.; 1982]: Book of Armory of the Kingdom of Navarra: Introduction, Study, and Notes.

- [Ailes, A.; 1982]: The Origins of the Royal Arms of England: Their Development to 1199.

- [Humphery-Smith, C.; 1983]: Why three Leopards?.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 1985]: Rare and Ambiguous Charges of Spanish Heraldry.

- [Becher, C.; Gamber, O.; 1986]: Die Wappenbücher Herzog Albrechts VI. von Österreich: Ingeram-Codex der ehem, Bibliothek Cotta, Volume 1.

- [Friar, S.; 1987]: A Dictionary of Heraldry.

- [Volborth, C. A. von; 1987]: The Art of Heraldry.

- [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1987]: Repertorio de blasones de la comunidad hispánica.

- [Guimera López, C.; 1987]: El Conde de Mora y la Heráldica.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 1988]: Spanish Heraldic Panorama: Epochs and Regions in the Medieval Period.

- [Burke, B.; 1989]: The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales; Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time.

- [Parsons, R. J.; 1989]: The Herald Painter.

- [Messía de la Cerda y Pita, L.; 1990]: Heráldica española, el diseño heráldico.

- [Mogrobejo Zabala, E. de; 1991]: Blasones y Linajes de Euskalerria.

- [Royal Spanish Academy; 1992]: Diccionario de la lengua española.

- [Herrera Casado, A.; 1993]: The Armorial of Aragon.

- [Sarandeses Pérez, F.; 1994]: Heraldry of Asturian Surnames.

- [Ferrer i Vives, F.; 1995]: Heraldica Catalana.

- [Emblemata; 1995]: Emblemata.

- [Arco y García, F. del; 1996a]: Introducción a la Heráldica.

- [Arco y García, F. del; 1996b]: Método de blasonar.

- [Emblemata; 1996]: Emblemata.

- [Rowling, J. K.; 1997]: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

- [Brault, G. J.; 1997]: Rolls of Arms of Edward I, 1272-1307, Volume I and Volume II.

- [Pastoureau, M.; Garvie, F.; 1997]: Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning.

- [Emblemata; 1997]: Emblemata.

- [GDLC; 1998]: Gran diccionari de la llengua catalana.

- [Emblemata; 1998]: Emblemata.

- [Académie internationale d'héraldique; 1999]: Mémorial du Jubilé, 1949-1999.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 1999]: Lions and Castles: Heraldic Emblems in Spain.

- [Zamora Vicente, A.; 1999]: Historia de la Real Academia Española.

- [Rabbow, A.; 1999]: The Origin of the Royal Arms of England - a European Connection.

- [Emblemata; 1999]: Emblemata.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; Martínez de Aguirre, J.; 2000]: The Coat of Arms of Navarra.

- [Emblemata; 2000]: Emblemata.

- [Sevilla Gómez, A.; 2000]: Las paremias heroicas: la divisa, el lema y el mote.

Century XXI:

- [Valverde Ogallar, P. B.; 2001]: Manuscripts and Heraldry in the Transition to Modernity: The Armory Book of Diego Hernández de Mendoza.

- [Martinena Ruiz, J. J.; Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 2001]: Book of Armory of the Kingdom of Navarra.

- [Emblemata; 2001]: Emblemata.

- [Royal Spanish Academy; 2001]: Diccionario de la lengua española.

- [Riesco de Iturri, M. B.; 2002]: Nobility and Lordships in Central-Eastern Castile in the Late Middle Ages (14th and 15th Centuries).

- [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 2002]: Diccionario heráldico: Términos, Piezas y Figuras Usadas en la Ciencia del Blasón.

- [Emblemata; 2002]: Emblemata.

- [Martín Fuertes, J. A.; 2002]: El Signum Regís en el Reino de León (1157-1230), Notas Sobre su Simbolismo (I).

- [Emblemata; 2003]: Emblemata.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; Márquez de la Plata, V. M.; 2003]: Simbología y diseño de la heráldica gentilicia galaica.

- [Emblemata; 2004]: Emblemata.

- [Alonso Gamo, J. M.; 2004]: Cayo Valerio Catulo: Poesías Completas.

- [Greaves, K.; 2005]: A Guide to Basic Blazonry.

- [Selvester, G. W.; 2005]: Aspects of Heraldry in the Catholic Church.

- [Emblemata; 2005]: Emblemata.

- [de Pando Villarroya, J. L. P. V.; 2006]: Historical Sciences, Heraldic Terms.

- [Emblemata; 2006]: Emblemata.

- [Sanz Lacorte, J.; 2007]: Glosario Heráldico.

- [Col, J. J. del; 2007]: Auxiliary Dictionary: Spanish-Latin for Modern Latin Use.

- [Emblemata; 2007]: Emblemata.

- [Martínez de Aguirre, J.; 2007]: Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués: Researcher of Navarrese Heraldry.

- [Vivar del Riego, J. A.; 2007]: El Blasón Escrito: La Historia de los Libros de Heráldica.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2007]: Análisis de las características generales de la heráldica gentilicia española y de las singularidades heráldicas existentes entre los diversos territorios históricos hispanos.

- [Emblemata; 2008]: Emblemata.

- [Domínguez García, J.; 2008]: Memorias del futuro: ideología y ficción en el símbolo de Santiago Apóstol.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2008]: Automatic painting 1991/2004, 210 paintings with ink, watercolor and other media.

- [Cox, N.; 2009]: The principles of international law governing the Sovereign authority for the creation and administration of Orders of Chivalry.

- [Vera-Ortiz, J.A.; 2009]: Linaje emeritense de don Juan Antonio de Vera y Zúñiga, un pícaro conde genealogista y una creencia muy arraigada.

- [Burke, B.; 2009]: The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales; Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time.

- [Emblemata; 2009]: Emblemata.

- [Kleisner, T.; 2009]: Amat Victoria Curam: The Device of Archduke Matthias on his Medals.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2009b]: Los Castillos en la Heráldica.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2009a]: Los Castillos en la Heráldica Española.

- [Sánchez Badiola, J. J.; 2010]: Símbolos de España y de sus regiones y autonomías: Emblemática territorial española.

- [Bakala, K.; 2010]: Historia symboliczna: znakiem, herbem i barwa pisana : podreczny slownik.

- [Parker, J.; 2010]: A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry, a New Edition with one Thousand Illustrations.

- [Emblemata; 2010]: Emblemata.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2010]: El Lobo, singularidad de la heráldica hispana.

- [García-Mercadal y García-Loygorri, F.; 2010]: Penas, Distinciones y Recompensas: Nuevas Reflexiones en torno al Derecho Premial.

- [Garaycoa Raffo, L.; 2011]: Contribución Heraldica para el Estudio de la Sociedad Colonial de Guayaquil.

- [Emblemata; 2011]: Emblemata.

- [Clemmensen, S.; 2012]: The St. Gallen-Haggenberg Armorial: Introduction and Edition.

- [Froger, M.; 2012]: L'héraldique: histoire, blasonnement et règles.

- [Marecki, J.; 2012]: Barwa w heraldyce.

- [Redakcja, P.; Mareckiego, J.; Rotter, L.; 2012]: Symbol - Snak - Przeslanie: Barwy i Ksztalty.

- [Emblemata; 2012]: Emblemata.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2012a]: El Hombre en la Heráldica.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2012b]: Las Figuras Humanas en la Heráldica.

- [García-Mercadal y García-Loygorri, F.; 2012]: La Regulación Jurídica de las Armerías: Apuntes de Derecho Heráldico Español.

- [Emblemata; 2013]: Emblemata.

- [Goldstraw, M. S. J.; 2013a]: The Heraldic Visitations of Cheshire 1533 to 1580.

- [Goldstraw, M. S. J.; 2013b]: The Heraldic Visitations of Cheshire 1613.

- [The Heraldry Society; 2013]: Education Pack, A brief explanation of Heraldry for teachers together with explanatory sheets and templates for students.

- [Vivar del Riego, J. A.; 2014]: Taller de Heráldica: Cómo diseñar y describir un escudo.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 2014a]: Los emblemas heráldicos: novecientos años de historia.

- [Greaves, K.; 2014]: A Guide to Blazonry.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2014b]: The Book of the Coat of Arms of Wolves Sable and Unicorns Argent.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2014a]: Design of the coats of arms o-XI, o-IX, o-XX with their crest, supporters, flags, seals and blazons.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2014]: El Bestiario Heráldico Balear.

- [Royal Spanish Academy; 2014]: Diccionario de la lengua española.

- [Fernández-Xesta y Vázquez, E.; 2014a]: Emblemática en Aragón. La colección de piezas emblemáticas del archivo biblioteca del Barón de Valdeolivos.

- [Fernández-Xesta y Vázquez, E.; 2014b]: Emblemática en Aragón. La colección de piezas emblemáticas del archivo biblioteca del Barón de Valdeolivos.

- [Pennick, N.; 2015]: Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies.

- [Emblemata; 2015]: Emblemata.

- [García-Mercadal y García-Loygorri, F.; 2015]: Catálogo emblemático del archivo-biblioteca del barón de Valdeolivos de Fonz.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2015a]: Coat of arms and heraldic creation between April 2014 and March 2015.

- [Serra i Rosell, P.; 2016]: Transmission of armorial bearings in the Kingdom of Castile in the 13th century. The arms of Don Enrique de Castilla, son of Fernando III the Saint..

- [Torres, A. V.; 2016]: Handbook Of The Order Of The Knights Of Rizal.

- [The Heraldry Society; 2016]: HeraldryForBeginners: Beasts, Banners and Badges.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2016a]: Coat of arms and heraldic creation between April 2015 and December 2016.

- [Emblemata; 2016]: Emblemata.

- [Williams, N.; 2017]: Irish Heraldry: A Brief Introduction.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2017b]: Coat of arms and heraldic creation between January 2017 and November 2017.

- [Emblemata; 2017]: Emblemata.

- [Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, F.; 2018]: Los sellos en nuestra Historia.

- [Emblemata; 2018]: Emblemata.

- [Conway, D. J.; 2018]: Magickal, Mystical Creatures: Invite Their Powers into Your Life.

- [The Heraldry Society; 2018]: Historic Heraldry Handbook.

- [Labara Ballestar, V. C.; 2019]: The municipal symbols of Candasnos (Huesca).

- [Mayoralgo y Lodo, J. M. de; 2019]: The Nobility of Cáceres and Their Armories.

- [Emblemata; 2019]: Emblemata.

- [Juby, B.; 2019]: The Splendour of the Modern Heraldic Bookplate Artist.

- [Grothues, B.; 2019]: Dr. Antonio Salmerón, heraldicus in Spanje. Een kijkje in het atelier van een heraldisch kunstenaar.

- [Gifra, V; Onida, G. C.; 2020]: Armoriale di Frugarolo e del territorio (con 330 stemmi raffigurati a colori).

- [Armorial Register, T.; 2020]: International Register of Arms, Volume Three, a Selection of Coats of Arms Conforming to the Laws of Heraldry and Recorded in the Private Register Held by The Armorial Register Limited.

- [Tosta, M. L.; 2021]: Los Tosta en Venezuela y en el mundo.

- [Halkosaari, H.; Prica, D.; 2023]: Aspilogia Discordiae 2022, A collection of armorial bearings from the Heraldry Community.

- [Gauci, C. A.; 2023]: The Way Forward.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2024b]: Interpretation of Six Family Coats of Arms from the Southern Indies Granted between 1538 and 1540.

- [Merrigan, M.; 2024]: Heraldry and Marriage Equality.

- [Huidobro Moya, J. M.; 2024]: La Heráldica Desconocida.

- [Salmerón Cabañas, A.; 2024a]: Coat of arms and heraldic creation between December 2017 and December 2023.

- [Christopher, N.; 2025]: The Regional Influence of Spanish Heraldry.

- [Gauci, C. A.; Cassar, R. M.; 2025]: The Register of Arms, Volume 1 (2019–2024).

- [Armorial Register, T.; 2025]: International Register of Arms, Volume Four, a Selection of Coats of Arms Conforming to the Laws of Heraldry and Recorded in the Private Register Held by The Armorial Register Limited.

- [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2025]: The Castles in Heraldry.

- [Académie internationale d'héraldique; 1952]: Vocabulaire-Atlas Héraldique en six Langues: Francais - English - Deutsch - Español - Italiano - Nederlandsch.

- [Hiltmann, T.; Hablot, L.; et alii; 2018]: Heraldic Artists and Painters in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times.

![Ver [Brutus of Britain, banner] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

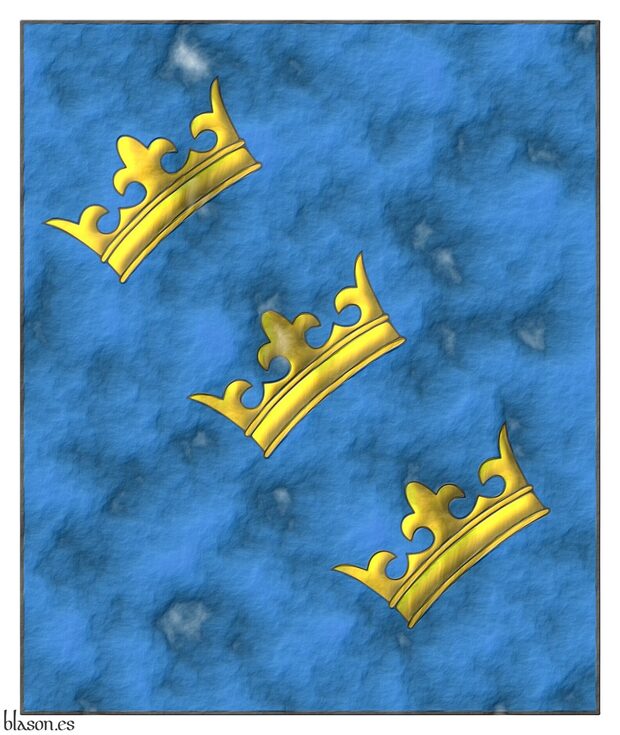

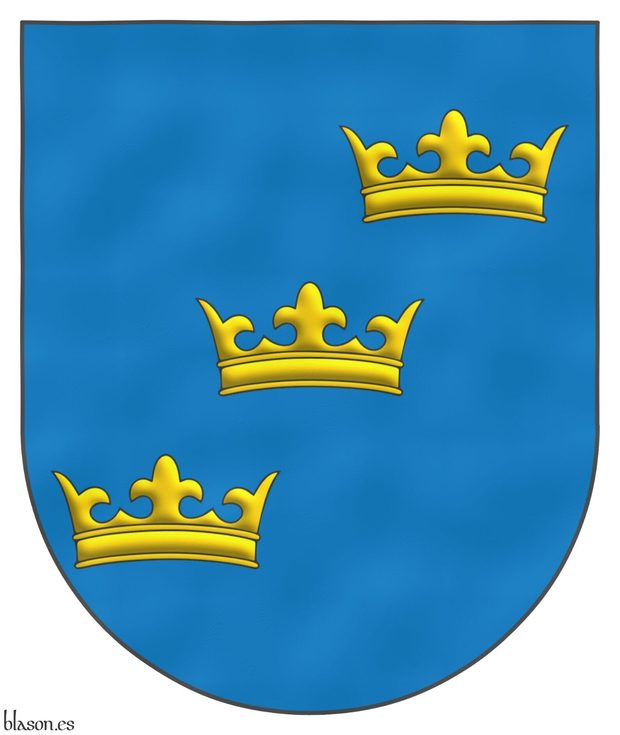

Brutus of Britain, banner

Banner Azure, three crowns in bend, bendwise Or.

Pendón de azur, tres coronas en banda, puestas en banda de oro.

Banner interpreted by me as follows: the field is enameled in plain Azure ink; the three crowns are outlined in Sable and illuminated in Or; and on old parchment.

Banner recreated from [Edward IV of England; 1461; row 13, 1st column].

Blazon keywords: Without divisions.

Style keywords: Rectangular, Illuminated, Outlined in sable and Crystalline.

Classification: Interpreted, Imaginary, Flag, Banner of arms, Kingdom of England and Criterion.

Imaginary bearer: Brutus of Britain.

![Ver [Castilian heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

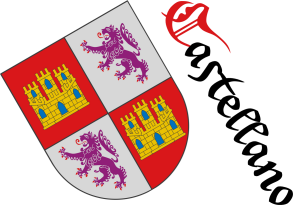

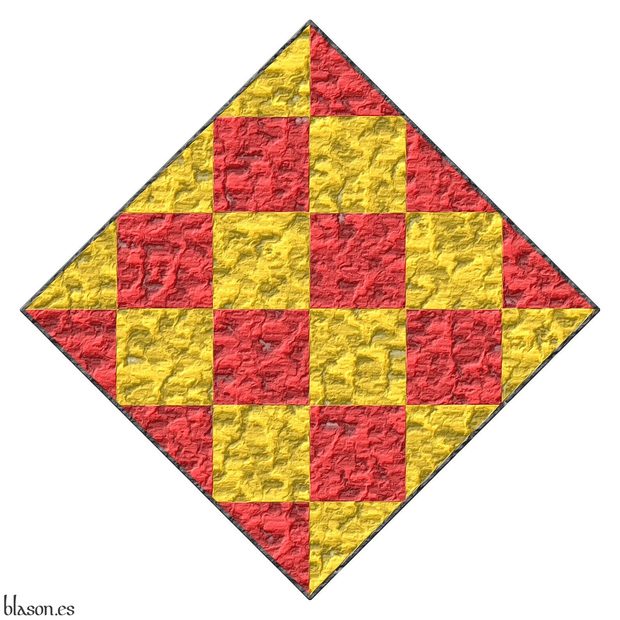

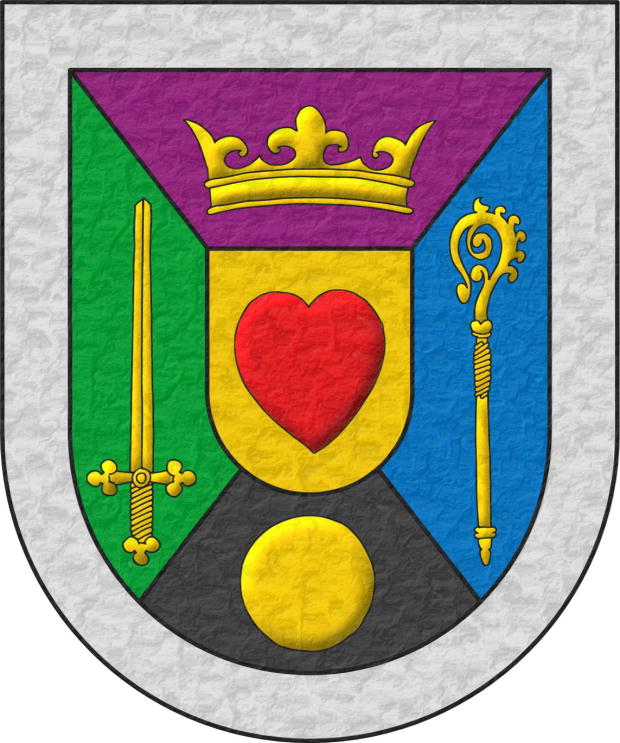

Castilian heraldry

Key Characteristics in Castilian Heraldry

Some of the main characteristics of the heraldry of Castile are:

- the rounded shapes, with a semicircle at the base,

- the importance of bordures,

- the inclusion of words and also letters in the coat of arms,

- the 2nd most common animal, after the lion, is the wolf [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2010], and, of course,

- our castle triple-towered Or, port and windows Azure, masoned Sable [Valero de Bernabé, L.; 2009a].

The following image shows 4 examples of coats of arms, each of which has some of these characteristics, including one Castilian castle.

Comparing Castilian and English Heraldry

In the United Kingdom, there are several heraldic traditions, one of them being English heraldry.

In the Kingdom of Spain, there are several heraldic traditions, for example, the Castilian tradition.

In my humble opinion, we should compare at the same level, English heraldry with, for example, Castilian heraldry, but not with all Spanish heraldry. We shouldn't do it for the same reason we don't mix Scottish heraldic tradition with English, as they are so different.

In the case of Castilian heraldry, the 8 main differences with English heraldry are:

- The rounded shapes, with a semicircle at the base.

- The importance of bordures and the existence of the diminished bordure, called in Castilian «filiera».

- The inclusion of words and also letters in the coats of arms.

- The wolf is the 2nd most common animal, after the lion.

- The castle, triple-towered, which is different from the English and French types of castles.

- We can inherit arms from our mother and/or father; for example, the castle in the 1st quarter of the coat of arms of Castile and the coat of arms of Spain comes from a mother, Queen Berenguela of Castile, mother of King Fernando III, the Saint.

- There are 3 kinds of supporters with their owns heraldic names: «tenantes», human forms; «soportes», animals; and «sostenes», plants and things.

- Our quarterings do not necessarily mean that the arms are marshalled by inheritance. [Williams, N.; 2017; page 135, paragraph 26.02] describing the arms of Éamon de Valera, 1882-1975, President of Ireland, writes «Those arms are Spanish in appearance. The quartering without functions as a means of marshalling, is distinctively Iberian».

Categories: Criterion, Semi-circular, Bordure, Letter, Lion, Wolf, Castle, Triple-towered, Port and windows, Masoned, Or, Azure, Sable, Diminished bordure, Quarterly, Supporter (human form), Supporter, Supporter (animal) and Supporter (thing).

![Ver [Chequey, chequy or checky] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

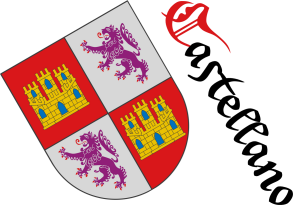

Chequey, chequy or checky

Chequey.

Chequey Or and Gules.

Escudo ajedrezado de oro y gules.

I have encountered several ways of writing the term «chequey» in English, such as «chequy», removing one «e», or «checky», and even other variants like «checkered», «checkie», «chequered», «cheque», «cheques» or «checquy».

[The Heraldry Society; 2013; pages 8 and 11] uses the term «chequey», and that is the one I strive to use.

Categories: Criterion, Tiled, Plain tincture, Hard metal, Chequey, Or and Gules.

![Ver [Eight-ball, another version with a terrace in base] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Eight-ball, another version with a terrace in base

Or, an eight-ball proper on a terrace in base Vert.

Escudo de oro, una bola ocho al natural terrazada de sinople.

Can modern objects appear in a coat of arms?

My rule is: a coat of arms is forever, so any symbol included must be recognizable by future generations. Can you place an iPhone in a coat of arms? No—but not because it’s modern, rather because your grandchildren likely won’t recognize the form of an iPhone; in fact, today’s mobile phones already look quite different from those of a decade ago. Can you include a steam locomotive? Yes, because its form has become anchored in time and in the collective imagination. What about an hourglass, an analog clock, or a black 8-ball from pool? Also yes—their forms are now classics. That is, I believe we can use those symbols that most people already carry in their minds and that are very likely to remain present in the minds of our children and grandchildren. But this is just my humble criterion.

Categories: Criterion, Art, Created, Imaginary, Coat of arms, Semi-circular, Crystalline, Soft metal, Outlined in sable, Illuminated, Without divisions, Or, One, Non-classic artifact, Proper and Terrace in base.

Root: Bola 8.

![Ver [Empresa, conjunto de cargas sobre el campo] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Empresa, conjunto de cargas sobre el campo

En Don Quijote, [Cervantes Saavedra, M. de; 1605; volumen 1, capítulo 18], el escudo de armas del «duque de Nerbia» se describe utilizando la palabra «empresa»~«enterprise», escribiendo «las armas de los veros azules», refiriéndose al forro de su escudo de armas, «es el poderoso duque de Nerbia, Espartafilardo del Bosque, que trae por empresa en el escudo una esparraguera, con una letra en castellano que dice así: «Rastrea mi suerte»».

Unas líneas antes, y para el joven caballero francés Pierres Papín, con un escudo sencillo de plata sin cargas ni lema, Cervantes escribe sin «empresa»: «que trae las armas como nieve blancas y el escudo blanco y sin empresa alguna».

Cervantes utiliza «empresa» para referirse únicamente a las cargas del escudo de armas, no al campo, ni a su color, metal o forro, ni al lema, lo cual queda claro cuando escribe: «Y desta manera fue nombrando muchos caballeros del uno y del otro escuadrón que él se imaginaba, y a todos les dio sus armas, colores, empresas y motes...».

El término se utiliza con el mismo significado de «carga en el escudo de armas» en el comentario al final de [Febrer, J.; Siglo XIII; trova 39] que dice «y quiso significarle con el puente, que traía por empresa en su escudo», siendo en este caso la carga el puente.

La quinta acepción del término «empresa» en el diccionario [Real Academia Española; 2014] es «Símbolo o figura que alude a lo que se intenta conseguir o denota alguna cualidad de la que se hace alarde, acompañada frecuentemente de un lema», que si bien no se refiere específicamente a la heráldica, está en línea con el uso anterior y deja claro que el lema no es parte de la «empresa» aunque puede acompañarla.

Por tanto, en castellano, el término «empresa» se refiere específicamente a la carga o cargas sobre el campo de un escudo de armas, y no incluye los esmaltes del campo, el lema, ni sus ornamentos exteriores.

Category: Criterion.

![Ver [Enterprise, set of charges on the field] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Enterprise, set of charges on the field

In Don Quixote, [Cervantes Saavedra, M. de; 1605; volume 1, chapter 18], the coat of arms of the «duke of Nerbia» is described using the word «empresa»~«enterprise», writing «las armas de los veros azules», referring to the fur on his coat of arms, «es el poderoso duque de Nerbia, Espartafilardo del Bosque, que trae por empresa en el escudo una esparraguera, con una letra en castellano que dice así: «Rastrea mi suerte»» ~ «the blue vair arms, is the powerful duke of Nerbia, Espartafilardo del Bosque, who bears as a charge on his shield an asparagus plant, with an inscription in Castilian that says: «Tracks my fate»».

A few lines before, and for the young French knight Pierres Papín, with simple arms Argent without charges or motto, Cervantes writes without «empresa»: «que trae las armas como nieve blancas y el escudo blanco y sin empresa alguna» ~ «who bears arms as white as snow and a shield white and without any charges».

Cervantes uses «empresa» to mean only the charges on the coat of arms, not the field, nor its color, metal or fur, nor the motto, which is clear when he writes: «Y desta manera fue nombrando muchos caballeros del uno y del otro escuadrón que él se imaginaba, y a todos les dio sus armas, colores, empresas y motes...» ~ «And in this way, he went on naming many knights from one and the other squadron that he imagined, and to each of them, he gave arms, colors, charges, and mottos...».

The term is used with the same meaning of «charge on the coar of arms» in the commentary at the end of [Febrer, J.; Siglo XIII; trova 39] which says «y quiso significarle con el puente, que traía por empresa en su escudo» ~ «and wanted to signify with the bridge that he bore as a charge on his shield», where in this case, the charge is the bridge.

The fifth definition of the term «empresa» in the dictionary [Real Academia Española; 2014] is «Símbolo o figura que alude a lo que se intenta conseguir o denota alguna cualidad de la que se hace alarde, acompañada frecuentemente de un lema» ~ «Symbol or figure that alludes to what one intends to achieve or denotes a quality of which one boasts, often accompanied by a motto», which, while not specific to heraldry, aligns with the previous usage and makes it clear that the motto is not part of the «empresa» though it may accompany it.

Then, in Castilian, the term «empresa» refers specifically to the charge or charges on the field of a coat of arms, and it does not include the field tinctures, the motto, or its external ornaments.

Category: Criterion.

![Ver [Flanched, schemaat one-third] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

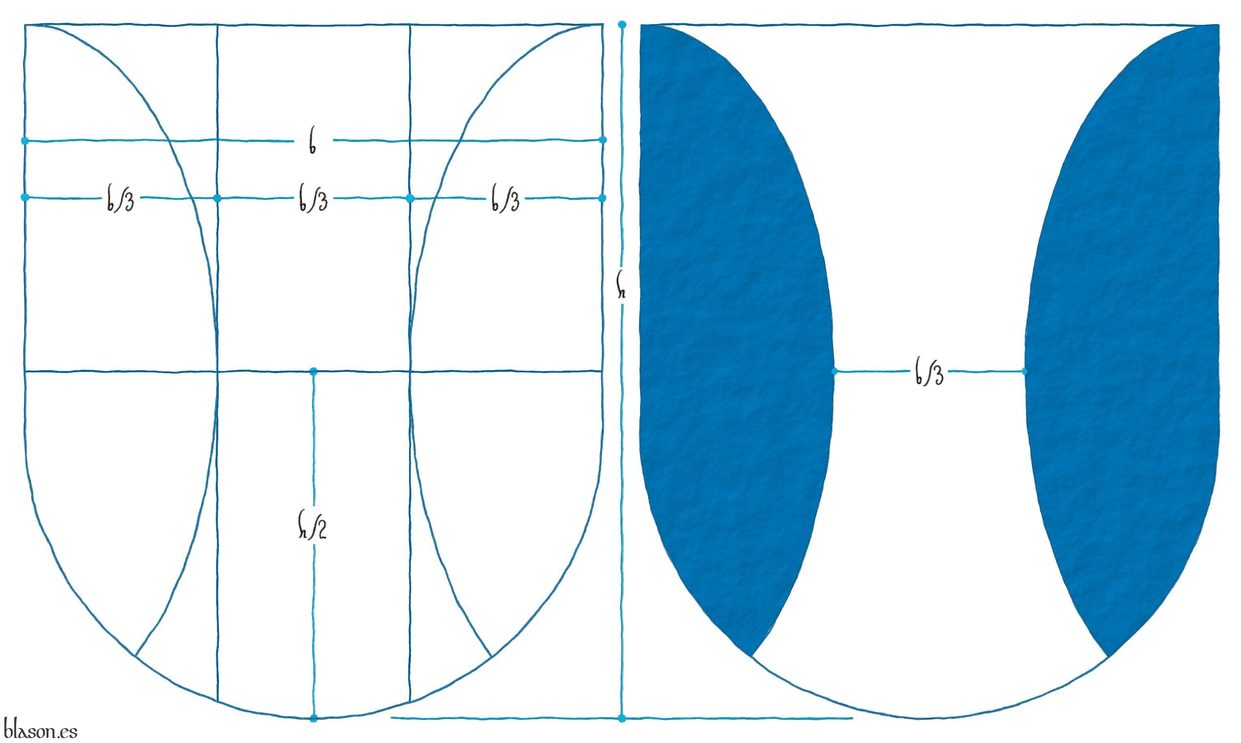

Flanched, schemaat one-third

Outlines and proportions of a flanched design at one-third.

This is my standardized way of delineating curved flanches, so that they remain tangent to a pale and, therefore, the width of both curved flanches and the space between them is equal to one third of the base. Some draw the flanches using circles, but I believe they look better as two half-ovals, which together would form a complete oval, with the height equal to that of the shield and the width two thirds of the base of the shield, that is, one third for each of the flanches, as in the figures illustrating this article. However, it should be noted that, depending on the charges, the separation distance may be adjusted.

Types of flanched designs

The «flanqueado curvo» corresponds to «flanched» in English, since for them the curved form is the default. [Avilés, J.; 1725b; page 92, figure 197] calls it «flanqueado en óvalo».

The «flanqueado apuntado» formed by 2 opposed triangles I call «pointed flanched» in English, as I have not found a better term. [Avilés, J.; 1725b; page 92, figure 198] calls it «flanqueado en sotuer», but what he draws in his book actually corresponds to a «cuartelado en sotuer» since the two points of the flanking meet at the center of the coat of arms.

«Flanqueado» without adjectives corresponds in Castilian to an «adiestrado» as opposed to a «siniestrado», and I refer to it in English as «flanked by two pales» having found no better translation.

Blazon keywords: Flanched.

Style keywords: Semi-circular.

Classification: Criterion and Schema.

Bearer: Oschoven of the Rhin.

![Ver [Governance heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Governance heraldry

Within governance heraldry, I classify the arms of states, as political structures, and those of their powers, their governing and administrative institutions, and their organizational substructures, such as regions, provinces, municipalities, etc.

The arms of Bosnia and Herzegovina, of Bunyoro-Kitara, and of Ceuta are examples of political heraldry.

This class partially coincides with what [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1975; page 87] refers to as «institutional heraldry».

Categories: Criterion and Civic.

![Ver [Heraldic classification] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Heraldic classification

I classify the coats of arms that I interpret or create depending on the field of the bearer of these armories and I do so within one of the following six categories:

- Personal heraldry.

- Governance heraldry.

- Military heraldry.

- Religious heraldry.

- Socioeconomic heraldry.

- Imaginary heraldry.

With their similarities and differences, there are many classifications within heraldry, some of which come from recognized authors. This specific classification, presented here, does not aim to be more than my personal way of classifying and organizing the coats of arms that I interpret or create.

As with any classification structure within a varied and rich universe of occurrences, as is the case with heraldry, there are always specific instances that belong or may belong to 2 or more classes, in these cases, I include the coat of arms in the one that seems most reasonable and provides the quickest and most logical location.

It could be suggested that this classification corresponds to the human being, in personal heraldry, and to their four most characteristic ways of organizing from a heraldic perspective: a) political and governance structures, b) military, c) spiritual and religious, and d) those of an economic or social nature. Allowing, in a sixth and final section of imaginary heraldry, for those creations of impossible ownership, on the border of heraldry and which, despite this, we do not want to exclude. The appeal of imaginary heraldry is that it is like a blank canvas on which we can create a coat of arms for someone or something with more freedom than in the other classes.

Imaginary coat of arms that encompasses the 6 classes of heraldry.

The quartered in saltire shield that illustrates this article symbolizes these 6 classes of heraldry:

- In the escutcheon of Or, a heart Gules symbolizes personal heraldry, the nobility of people, the love of family, and the blood of lineage.

- The 1st of Purpure and the crown Or represent political and governance structures and their heraldry, with Purpure being a color associated with power since Roman times.

- The 2nd of Vert and the sword point upwards Or, in open field, a vert battlefield, symbolizes military heraldry.

- The 3rd of Azure, the color of the sky, and the crozier Or is the representation of religious heraldry.

- The 4th of Sable, reminiscent of an industrial or mining ground, and a bezant, always Or, representing currency and money, symbolizes socioeconomic heraldry.

- The bordure Argent, as an outer border, frontier, or blank canvas, is the proper domain of imaginary heraldry.

Reflections on governance heraldry

In my approach to heraldry, I choose to unify political and civic heraldry under the broader concept of «governance heraldry». While modern terminology often distinguishes «civic heraldry» as a separate entity, with professionals focusing specifically on municipal arms, I see a deeper connection. Historically, the heraldry of kingdoms and kings was frequently intertwined; the arms of regions or realms were quartered to create the arms of united kingdoms. These kingdoms were often divided into regions and provinces, with cities frequently founded by royal orders and granted certain privileges.

Thus, I bring all of these elements together under the concept of «governance heraldry», in Castilian «heráldica política». Although in English this is often translated as «civic heraldry» to align with contemporary usage, a more precise term might be «political and civic heraldry». However, this combination does not fully convey the interconnectedness of all forms of heraldic expression related to governance, whether at the level of a kingdom, region, or municipality.

Category: Criterion.

![Ver [Imaginary heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Imaginary heraldry

Within imaginary heraldry, I classify the arms attributed to persons, entities, or things, real, mythical, or imaginary, that could not or cannot possess them, or if they did, their existence is unknown, or due to various circumstances, they neither could nor can assume them.

For example, the coat of arms of Odysseus of Ithaca, legendary hero of Greek mythology, of Brutus of Britain, mythical hero of Troy and founder of Britain who never existed, of Seneca, who historically existed, but could not have had arms as he lived before heraldry, of Hufflepuff at Hogwarts from the Harry Potter books, of the Holy Trinity, of logic, of arithmetic, or of the categories of heraldry.

Categories: Criterion and Imaginary.

![Ver [In bend sinister and palewise] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

In bend sinister and palewise

Azure, three crowns in bend sinister, palewise Or.

Escudo de azur, tres coronas en barra, puestas en palo de oro.

Since the crowns are in bend sinister and the main axis of the crown is vertical, they are naturally placed palewise, but in this case, being in bend sinister, I prefer to specify it in the blazon.

- In bend sinister ~ en barra.

- Palewise ~ Puesto en palo.

Blazon keywords: Without divisions, Azure, Or, Crown, In bend sinister and Palewise.

Style keywords: Semi-circular, Outlined in sable and Watercolor.

Classification: Criterion.

Bearer: In and wise.

![Ver [Latidos Podencos] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Latidos Podencos

Gules: a warren hound parado statant Or; a base hearty Or.

Escudo de gules: un podenco parado de oro; la campaña encajada de corazones de oro.

Coat of arms that I have created with: the shield’s shape pointed and rounded; its field painted in flat tint gules; the warren hound and the base hearty are illuminated Or and delineated Sable; and the whole is executed in raised-line drawing.

Symbolism

A base made of generous hearts Or, interlocked with hearts Gules, red as blood, gives its support to a Spanish warren hound standing upon it. They are the hearts of those who love, protect and care for the hounds, intertwined with the hearts of the hounds whose noble heartbeats are evoked in the motto.

The founders of this Spanish warren hound shelter did not wish for a dog armed and langued, since those heraldic attributes would imply that the animal is not truly in need of protection. They preferred instead to highlight the podenco’s loyalty and faithfulness.

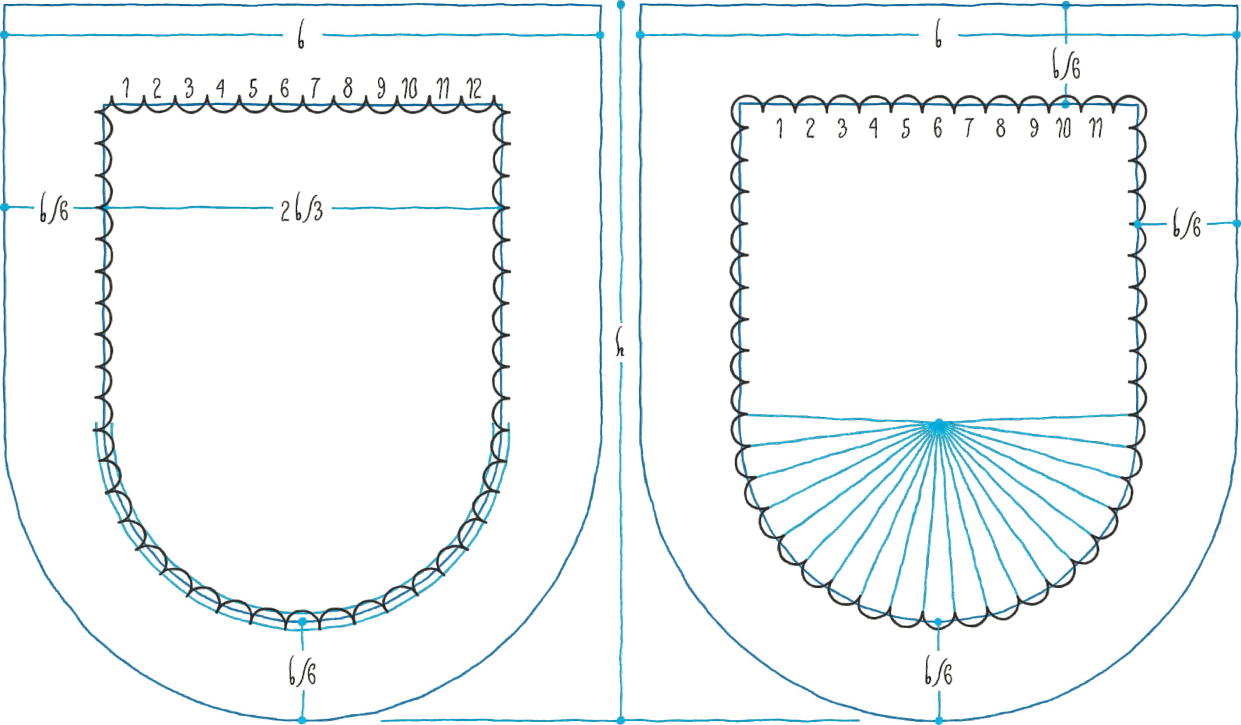

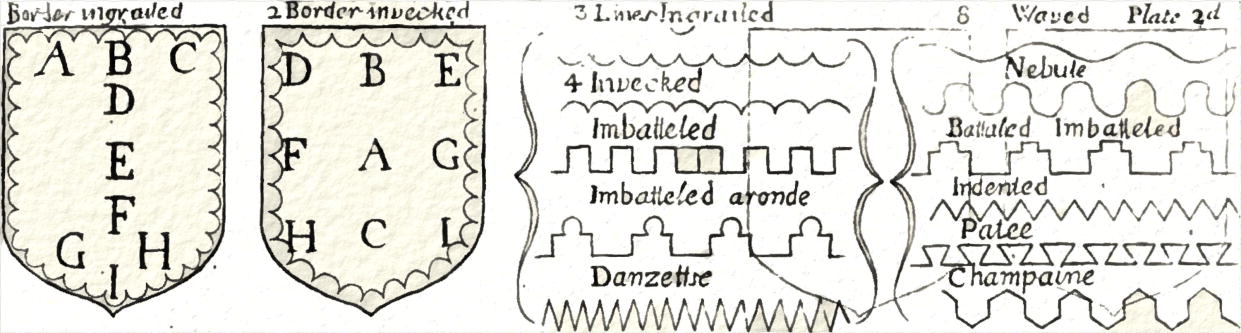

Types of lines of division

In English heraldry, ordinary lines of partition such as «almenado» ~ «embattled», «acanalado» ~ «invected», or «angrelado» ~ «engrailed» have well-established names. There is, however, no general rule for blazoning lines formed by repeated and more elaborate figures, such as fir trees, fleurs de lis, or other shapes.

Each case tends to receive a descriptive or newly coined term, such as «sapiné» or «flory» «flory counterflory», in these last two cases depending on whether the figures all point in one direction or alternate upward and downward.

Note that in «sapiné» the charm lies precisely in that alternation: the fir trees point alternately upward and downward, so that the figures interlock with each other.

Therefore, if a new figure appears, such as the heart in this case, with hearts pointing upward, one might say «hearty» or, more specifically, «hearty counterhearty»; but following the example of «sapiné», we shall simply blazon «hearty».

For example, the line formed by dovetail shapes, called «dovetailed» in English, is blazoned in Spanish as «encajada de colas de milano», even changing the name of the bird. Note that in this case they interlock precisely because some point upward and others downward, hence their use in joinery, cabinetry, and related arts.

In Spanish there are classical terms for the most common forms, such as «almenado», «acanalado» or «angrelado», with «encajado» ~ «dancetty» being perhaps the most characteristic, where the angles interlock alternately upward and downward.

When facing new or uncommon shapes, instead of inventing a new term we prefer to use the basic one, «encajado», adding afterwards the specific figure that forms the interlock, for example, «encajado de abetos» ~ «sapiné».

Thus, in this case we blazon «the base hearty», with the hearts alternating upward and downward, just as in the traditional «encajado» the angles alternate both ways.

Blazon keywords: Without divisions, Gules, Or, Warren hound, Dog, Base, Base (lower 1/3), Dancetty and Heart.

Style keywords: Ogee, Illuminated, Outlined in sable and Freehand.

Classification: Created, Socioeconomic, Design rationale, Criterion and Coat of arms.

Bearer: Latidos Podencos.

![Ver [Military heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Military heraldry

Within military heraldry, I classify the arms of individuals, institutions, orders, military corps, and entities.

Although the military is an institution of the state, I dedicate a separate category to it in recognition of its special characteristics and history, as well as its particular functions of cohesion and identification, which are rooted in heraldry for the battlefield. The coat of arms of the Central Military Region and the Artillery Combat School of the Swedish Army are examples of military heraldry.

[Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1975; page 88] includes military heraldry within his «institutional heraldry».

Categories: Criterion and Military.

![Ver [Motto of Rolando Yñigo-Genio] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Motto of Rolando Yñigo-Genio

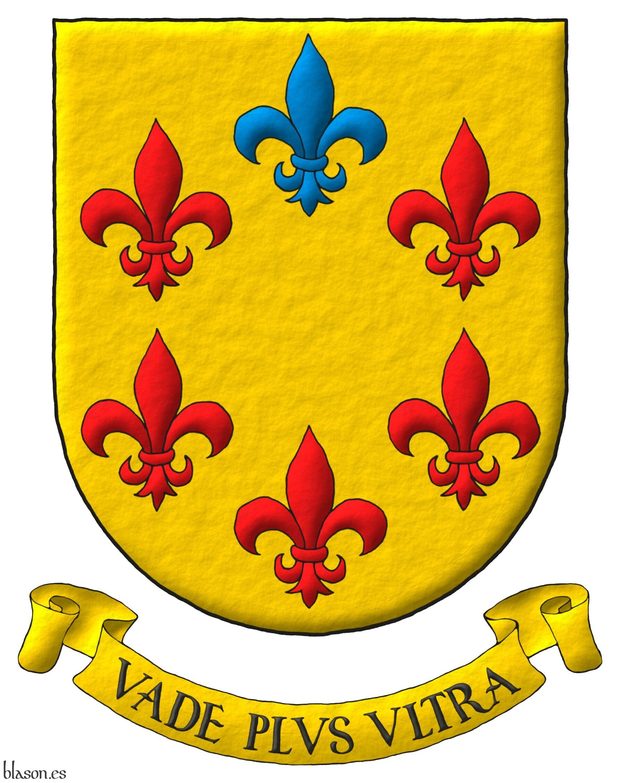

Or, six fleurs de lis in orle, five Gules and one in chief Azure. Motto: «Vade Plvs Vltra»

On the choice of language for the motto

The motto can be in any language. However, as a coat of arms is meant to last for eternity, living languages evolve, and the original meaning of the motto may be misinterpreted by future generations. For example, some words may eventually acquire unfortunate or inappropriate meanings over time. The advantage of dead languages, such as Latin, over living ones is that they do not evolve, and the meaning of the motto remains more resistant to the passage of time.

Credits: Rolando Yñigo-Genio is the designer of the coat of arms and Antonio Salmerón y Cabañas is the author of the heraldic art.

Categories: Criterion, Art, Interpreted, Personal, Semi-circular, Soft metal, Outlined in sable, Coat of arms, Or, Six, Fleur de lis, Orle, Five, Gules, One, Azure, In chief and Motto.

Root: Yñigo-Genio, Rolando.

![Ver [Personal Heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Personal Heraldry

Within personal heraldry, I classify the arms of individuals, their families, or lineages.

When a coat of arms representing a person, such as in the case of a king, is also used to represent something else, such as their kingdom, I classify it as personal heraldry, prioritizing the representation of the individual over other possible uses, as this is the origin of heraldry.

The historical arms of Carlos de la Cerda or the current ones of Austin Charles Berry and of Stephan Urs Breu are examples of personal heraldry.

In Spanish, I use the name given by [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1975; page 53] and in English «personal heraldry», which is the most commonly accepted term.

Categories: Criterion and Personal.

![Ver [Religious heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Religious heraldry

Within religious heraldry, I classify the arms of individuals, offices, dignitaries, institutions, communities, orders, and religious entities, primarily, by tradition, those of the Church.

The arms of the Order of Mercy and those of the Oratorio de San Felipe Neri are examples of religious heraldry.

Being more general, this category encompasses what [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1975; page 59] refers to as «ecclesiastical heraldry».

Categories: Criterion and Religious.

![Ver [Socioeconomic heraldry] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Socioeconomic heraldry

Within socioeconomic heraldry, I classify the arms of all collectives not included in the previous categories, such as, for example, commercial societies, which may represent companies, their brands, and products, sports clubs and federations, associations, professional colleges, educational institutions, arms granted or assumed collectively, etc.

For example, the coats of arms of universities, both private and public, belong to this category, the former naturally and the latter considering their appropriate autonomy from state powers. In this way, the coat of arms of the IESE, as a business school, is an example of socioeconomic heraldry.

Also included are the coats of arms of associations, like the Norsk Heraldisk Forening, and of companies, such as the arms of Alea Capital.

This category partially coincides with what [Cadenas y Vicent, V. de; 1975; page 119] refers to as «representative heraldry».

Categories: Criterion and Socioeconomic.

![Ver [Supporters with human forms from the city of Ubeda] en criterios utilizados. Unicornio saltante sobre la divisa, criterio.](../css/Unicornio.Criterio.png)

Supporters with human forms from the city of Ubeda

Selection of photos of supporters with human forms from the city of Ubeda, Jaen, Andalusia.

In international heraldry groups, I often notice that tenantes are discussed almost as a heraldic rarity, something very uncommon, reserved only for certain types of corporations or high-ranking individuals. This can be seen, for example, in phrases like «tenant is not a heraldic term, whereas supporter is» or humorous expressions such as «I do have tenants, they pay me rent» or «our tenants living on our land and who pay us rent do not wear our badges».

Therefore, to spread the idea that tenantes are not uncommon in Castilian heraldry, I thought a good image would be worth a thousand words. So, I created a montage of images from Úbeda alone and published it with the phrase «This is a selection of tenants photos from only one single city, Úbeda, Jaén, Andalusia», and I am sure that there are even more tenantes in Úbeda.

Categories: Criterion, Supporter (human form) and Supporter.

-

Language

-

Categories of heraldry

-

Divisions of the field

- Without divisions

- Party per pale

- Party per fess

- Party per bend

- Party per bend sinister

- Tierce

- Tierce sinister

- Tierced per pale

- Tierced per fess

- Tierced per bend

- Tierced pallwise inverted

- Quarterly

- Quarterly per saltire

- Gyronny

- Party per fess, the chief per pale

- Party per pale, the sinister per fess

- Party per fess, the base per pale

- Party per pale, the dexter per fess

- Chapé

- Chaussé

- Embrassé

- Contre-embrassé

- Party per chevron

- Enté

- Enté en point

- Flanched

-

Metals

-

Colours

-

Furs

-

Other tinctures

-

Ordinaries and sub-ordinaries

-

Diminutives of the ordinaries

-

Geometric charges

-

Composite ordinaries

-

Inanimate charges from Nature

Atom, Crescent, Diamond, Emerald, Estoile, Increscent, Lightning flash, Moon, Mount, Mullet, Mullet of four points, Orbital, Plough of Ursa Major, Rainbow, Ray of the sun, River, Sea, Snowflake, Sun, Sun in splendour, Sun of May, Terrestrial globe, Trimount, Water and Wave.

-

Vegetal charges from Nature

Acorn, Apple, Apple tree, Ash, Bluebonnet, Camellia, Chrysanthemum, Cinquefoil, Cornflower, Dogwood flower, Double rose, Eguzki-lore, Elm, Fleur de lis, Flower, Gourd, Holm oak, Hop cone, Indian paintbrush, Kapok tree, Laurel, Lily, Linden, Lotus flower, Madonna lily, Mexican cedar tree, Oak, Olive tree, Palm tree, Plantain plant, Pomegranate, Poplar leaf, Rose, Shamrock, Sunflower, Thistle, Tree, Tulip, Vine and Wheat.

-

Animal charges from Nature

Badger, Bald eagle, Barbel, Barn owl, Bear, Beaver, Bee, Beetle, Bighorn sheep, Binson, Blackbird, Boar, Brach hound, Bull, Cow, Doe, Dog, Dolphin, Dove, Eagle, Elephant, Falcon, Female figure, Fish, Flame, Fly, Fox, Frog, Goat, Goldfinch, Goose, Heron, Horse, Hummingbird, Jaguar, Lark, Leopard, Lion, Lion passant, Lion rampant guardant, Lioness, Lynx, Male figure, Martlet, Merino ram, Owl, Panther, Parrot, Peacock, Pelican, Pelican in her piety, Pronghorn, Puffin, Quetzal, Raven, Roe deer, Rooster, Savage, Seagull, Serpent, She-wolf, Stag, Starling, Talbot, Turtle, Tyger, Vulture, Warren hound and Wolf.

-

Parts of natural charges

Arm, Beak, Branch, Caboshed, Chest, Claw, Covert, Dorsal fin, Eagle claw, Ear of wheat, Ermine spot, Escallop, Feather, Foot (palmiped), Foreleg, Forepaw, Hand, Head, Heart, Hoof, Leaf, Neck, Ostrich feather, Palm frond, Paw, Roe deers' attires, Shoulder, Sprig, Stags' attires, Stem, Swallow-tail, Tail, Tail addorsed, Tail fin, Talon, Tibia, Tooth, Trunk, Trunk (elephant), Two hands clasped, Two wings in vol, Udder, Wing and Wrist.

-

Artificial charges

Ace of spades, Anchor, Anvil, Arch, Arm vambraced, Armillary sphere, Arrow, Axe, Bell, Bell tower, Beret, Bonfire, Book, Bookmark, Bow, Branding iron, Bridge, Broken, Buckle, Cannon, Cannon dismounted, Cannon port, Canopy roof, Carbuncle, Castle, Celtic Trinity knot, Chain, Chess rooks, Church, Clarion, Clay pot, Closed book, Club, Column, Comb, Compass rose, Conductor's baton, Cord, Covered cup, Crozier, Crucible, Cuffed, Cup, Cyclamor, Dagger, Displayed scroll, Double vajra, Drum, Ecclesiastical cap, Fanon, Federschwert, Fleam, Four crescents joined millsailwise, Galician granary, Garb, Gauntlet, Geometric solid, Grenade, Halberd, Hammer, Harp, Host, Hourglass, Key, Key ward, Knight, Knot, Lantern, Letter, Line, Loincloth, Maunch, Menorah, Millrind, Millstone, Millwheel, Monstrance, Mortar, Mullet of six points pierced, Nail, Non-classic artifact, Norman ship, Number, Oar, Oil lamp, Open book, Page, Pair of pliers, Pair of scales, Parchment, Pestle, Piano, Pilgrim's staff, Plough share, Polish winged hussar, Port, Portcullis, Potent, Quill, Ribbon, Rosette of acanthus leaves, Sabre, Sackbut, Sail, Scroll, Scythe, Sheaf of tobacco, Ship, Skirt, Spear, Spear's head, Stairway, Star of David, Step, Sword, Symbol, Tetrahedron, Torch, Tower, Trident, Trumpet, Turret, Two-handed sword, Wagon-wheel, Water-bouget, Wheel, Winnowing fan and With a turret.

-

Immaterial charges

Angel, Archangel, Basilisk, Dragon, Dragon's head, Garuda, Golden fleece, Griffin, Heart enflamed, Justice, Mermaid, Our Lady of Mercy, Ouroboros, Paschal lamb, Pegasus, Phoenix, Sacred Heart of Jesus, Saint George, Sea-griffin, Sea-lion, Trinity, Triton, Unicorn, Winged hand and Wyvern.

-

External elements

-

Heraldic creations

-

References

-

Formats

-

Keywords on this page

Invected, Port and windows, Watercolor, Chequey, Proper, Engrailed, Non-classic artifact, Azure, Flag, Bola 8, Bordure, Brutus of Britain, Base, Castilian heraldry, Castle, Five, Ogee, Heart, Crown, Created, Crystalline, Criterion, Quarterly, Triple-towered, Outlined in sable, In bend sinister, In chief, Dancetty, Coat of arms, Schema, Diminished bordure, Flanched, Fleur de lis, Personal, Gules, Illuminated, Imaginary, In and wise, Interpreted, Latidos Podencos, Motto, Semi-circular, Soft metal, Or, Without divisions, Socioeconomic, Supporter, Supporter (human form) and One.